My apologies that this page is a mind-dump. It will be edited in due course. I am trying to consolidate what I can find about Ottoman archives in one place, and then we can create a strategy for making research there simpler.

History of the Jews of Turkey and the Ottoman Empire

During the 1590s, the Ottoman Empire was at its largest extent and included all Muslim countries around the Mediterranean, except Morocco. It also encompassed Greece and the Balkan countries, stretching up to Hungary. Prior to the Expulsion of Sephardic Jews from Spain, there were already established Romaniote/Greek Jewish communities in the region, predating the Islamic conquest. Some of these were absorbed by the Sephardim. The Ottoman Empire was home to several important Sephardi communities, such as Constantinople (Istanbul) and Smyrna (Izmir) in modern-day Turkey, as well as Salonica (Thessaloniki), Rhodes, and Corfu

Sephardic Emigration from Turkey

The general situation of the Jewish community got worse as the Ottoman Empire declined. Phases of emigration seem to have been driven by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which made Egypt a better prospect than Turkey, and the social and political reforms after the Turkish republic was created in the 1920s. For trade reasons, branches of some families had moved in western Europe in the second half of the 19th Century, and then put down roots. Others chose to emigrate to the Americas.

A first step is to know where your Ottoman ancestors originated. The Cercle de Généalogie Juive in France publishes Destins de séfarades ottomans by Philippe Danan, with a preface by Edgar Morin. In most destination countries, census and naturalisation records are helpful.

Beyond Constantinople: The Memoirs of an Ottoman Jew is a memoir by Victor Eskenazi who was born in 1906.

To the Western Sephardim, the Eastern Sephardim of the Ottoman Empire were known as Levantinos. In turn, Western Sephardim were known by Eastern Sephardim as Francos.

Jewish Genealogy in Turkey

Jewish genealogy in Turkey remains challenging but is improving.

For Turkish citizens or people with Turkish cousins, the first stop should be the e-Devlet site. e-Devlet is the Turkish e-government gateway. It contains genealogical data. When the site was launched, interest in finding out about family history was so huge that the site crashed! This information is only accessible to Turkish citizens. This is the genealogical access page.

How should everyone else start? Obviously, with yourselves and known ancestors. Unfortunately, there is not a single, easily accessible, source of Jewish records in Turkey. The situation is made worse by Turkey’s privacy laws. Many Jewish archives for Turkey are now held by the Office of the Chief Rabbi, the Haham Bashi, but do not expect a speedy reply to information requests.

A recent project to digitise Turkish cemeteries has created a hugely valuable website: A World Beyond: Jewish Cemeteries in Turkey 1583-1990.

Abraham Galante’s nine-volume Histoire des Juifs de Turquie is an important resource. The index is searchable on the JewishGen website.

There is an old but still useful article by Dr. David Sheby – Ottoman Sephardic Genealogy: An Introduction – on the Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture website. See also The historiography of Ottoman Jewry by Yaron Ben-Naeh. Avigdor Levy has also written on Jews in Turkey.

The Sephardic Onomasticon: An Etymological Research on Sephardic Family Names of the Jews Living in Turkey by Baruh Pinto is the only book specifically on Turkish Sephardic surnames. It is not highly regarded. Alexander Beider is believed to be working on a book on eastern Sephardic surnames.

The records of the former Ottoman Empire remain a largely unexplored treasure trove. These are discussed below.

Jewish Constantinople / Istanbul

After the Ataturk revolution, the Jewish community of Istanbul was divided in two, the Grand Rabbinat managed religious matters, and the Conseil laïque managed finance and administration.

In 1940 the Beth Din comprised:

- Rev. R. Raphael Saban, President

- Rev. Dr David Marcus, President of the Ashkenazi CommunityRab. Moché Ben Habib

- Rab. Yaacov Arrouete

The Conseil laïque comprised:

- Henri Soriano, President

- H. Goldenberg, Vice President

- Marcel Franco

- Joseph Salmona

- Marco Nassi

- Isaac Rividi

- Me Refik Habib

- Albert Barocas

Jewish Smyrna / Izmir

The Great Fire of Smyrna, from 15 to 22 September 1922, marked the Turkish victory in the Greco-Turkish War. Before the catastrophe, George Horton estimated that the city had 25.000 Jews out of a total population of 400,000 people.

Jewish Marriages in Smyrna / Izmir

The surnames below are from a list of Jewish marriages in Smyrna / Izmir. Not all of the marriages are Sephardic. The library of the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain contains a copy of Dov Cohen’s “List of 7300 names of Jewish brides and grooms who married in Izmir 1883-1901 and 1918-1933”.

Aba, Abastado, Abistanche, Aboav, Aboressi, Abrameto, Abravanel, Abravaya, Abrevanel, Abrevaya, Abudraham, Abulafia, Aburei, Abut, Acher, Acrish, Adarto, Adato, Ades, Adjiman, Adrato, Adut, Aelion, Afias, Aji, Alacher, Aladjem, Alaluf, Alazraki, Albagli, Albahag, Albahari, Albalag, Albelda, Alboher, Alcalay, Alcheh, Alcolumbre, Alfandari, Alfissi, Algamis, Algarante, Algariani, Algaze, Algazi, Algranate, Alhadef, Alhanate, Alhanati, Alharal, Aliman, Alkahi, Almosnino, Almozlina, Almozlino, Altalef, Altina, Aluf, Alvalansi, Alvalansi-Tchakir, Amado, Amar, Amario, Amato, Amiel, Amira, Amiras, Amon, Amram, Angel, Angel-Atias, Antebe, Antica, Aptekman, Aradi, Araha, Arama, Arania, Ardit, Arditi, Arie, Arnaldes, Arnandes, Aroshas, Arueste, Arugueti, Aruh, Ashmid, Assa, Assael, Assaias, Assia, Assia-Antica, Assia-Antico, Assias, Assias-Antika, Assipov, Asubel, Asubel-Djigal, Atas, Atias, Avayu, Avigdor, Avimeleh, Avishai, Avraham, Avraham-Avinu, Avut, Avzaradel, Azar, Azicri, Azriel, Azulai, Badi, Baena, Baessa, Bakish, Bali, Bardavid, Barelia, Barelie, Barki, Barmaimon, Barnatan, Barnot, Barsimantov, Baruch, Baruch-Saban, Barzilai, Batino, Bedrishi, Bega, Begas, Behar, Behar-Avraham, Behar-Bodjuk, Behar-Botchuk, Behar-Daniel, Behar-David, Behar-Elia, Behar-Gavriel, Behar-Israel, Behar-Itzhak, Behar-Merendatcho, Behar-Mishael, Behar-Moshe, Behar-Ovadia, Behar-Ponpas, Behar-Refael, Behar-Shabetai, Behar-Shelomo, Behar-Shemuel, Behar-Yaacov, Behar-Yeoshua, Behar-Yomtov, Behar-Yossef, Behmoaras, Behor, Behor-Bodjuk, Beja, Beli, Belo, Benadava, Benaderet, Benamram, Benaroia, Benatar, Benavet, Benazuz, Bendaissos, Bendossa, Benezra, Benforado, Bengabay, Benguiat, Benhabib, Benjoia, Benkish, Benmaor, Benmayor, Benmuvhar, Bennahmias, Bennaim, Bennun, Benrei, Benreina, Benrubi, Bensasson, Benshoam, Bensinior, Bension, Bensussan, Benuzio, Benveniste, Benyakar, Benzif, Benzonana, Beraha, Bernar, Bernstain, Bero, Besso, Betzalel, Bezbon, Bichachi, Bile, Bili, Birioti, Biton, Bitran, Bodjuk, Boher, Bojuk, Bonana, Bondi, Bonfil, Bonomo, Bonpurgo, Botchuk, Boton, Buena, Buena-Vida, Bueno, Burgana, Burgo, Burla, Burlas, Burnavil, Cabili, Cabuli, Cadranel, Calabrez, Calatche, Calderon, Calev, Calmi, Calomiti, Calpo, Caluf, Calvo, Camhi, Campeas, Caneti, Canias, Canpeas, Canton, Capeluto, Capsuto, Caraco, Carasso, Cardoso, Cario, Carmona, Caro, Caspi, Cassuto, Castoriano, Castro, Catalan, Catan, Catarivas, Cavayero, Cavo, Cazes, Cezana, Chaki, Chaves, Cicurel, Civita, Cohen, Cohen-Arias, Cohen-Avishai, Cohen-Hemsi, Cohen-Itamari, Cohen-Nahar, Cohen-Rapoport, Cohen-Sirutchki, Colodro, Combriel, Comidi, Compolonguer, Conen, Confino, Confortes, Coni, Conin, Contente, Cordovero, Cori, Corkidi, Coronio, Costi, Cozi, Crespin, Crispin, Crudo, Cuenca, Cuencas, Cuencas-Franco, Culias, Cumbriel, Cunio, Curiel, Daian, Dalsa, Dalva, Dana, Daniel, Danon, Darsa, David, Del Burgo, Dente, Dentes, Deutch, Dias, Dias-Pereira, Dias-Shituvi, Diente, Dinar, Djelarden, Dof, Dolfo, Donio, Donoso, Donozo, Dozetas, Dozetos, Duenias, Efrati, El, Elazar, Elenbogen, Elhai, Elhaiki, Elhanan, Elhay, Eliezer, Elkana, Emanuel, Enguelbach, Enriques, Enriques-Sarano, Ergaz, Escapa, Esforno, Eskenazi, Esperansa, Estranski, Estrugo, Estrumsa, Evlagon, Ezovi, Ezra, Ezrati, Fais, Falcho, Falcon, Farage, Faragi, Farhi, Farnaldes, Feinbaum, Fernaldes, Fernandes, Ferrera, Fez, Filberg, Filossi, Firezi, Fleingenlemmer, Florentin, Frances, Francia, Francis, Franco, Frangi, Fresco, Fuertes, Funes, Gabay, Gagui, Gaguin, Galante, Galico, Galimidi, Galindo, Galindos, Gani, Ganon, Gaon, Gargui, Garguir, Gategno, Gatenio, Gavriel, Gayego, Gayero, Girassi, Goldemberg, Goldenberg, Gomel, Gortchi, Grassian, Greenberg, Grinber-Tzevi, Guershom, Guershon, Guini, Guizelter, Habibi, Habif, Hadjes, Hadjez, Haim, Hakim, Halegua, Haleo, Halfon, Halifa, Hanan, Hanania, Hanna, Hanna-Morat, Hara, Hassan, Hassid, Hassidof, Hasson, Hatem, Hay, Hayun, Hazan, Hefetz, Hefez, Herman, Heshpiter, Hilel, Hirschkovitch, Hoba, Hodara, Hodara-Perez, Hopa, Hova, Huli, Hulli, Ida, Idi, Ishbia, Ishmiel, Israel, Israel-Beraha, Issachar, Issahar, Itzhak, Itzhaki, Ivlagon, Jakum, Jesua, Kedoshim, Kubes, Kurtzberg, Kush, Lahana, Larede, Laros, Laroz, Leon, Lerea, Letche, Levy, Levy, Levy-Carasso, Levy-Mazlum, Levy-Shama, Lilo, Lilos, Limon, Lisbona, Lizmi, Lizmin, Lodrigues, Loria, Losa, Magriso, Magrisso, Magrizo, Mahalalel, Maio, Maish, Maizel, Maizi, Makanaz, Malal, Malki, Mantel, Marash, Marco, Marcos, Margonato, Markiof, Maskil, Masriel, Matalon, Matarasso, Matatia, Matcha, Matza, Matzliah, Mazal, Mazaltov, Mazon, Mecapua, Mecapua-Bengali, Mecapua-Bingli, Medico, Medina, Medini, Mehalalel, Meir, Melamed, Melo, Menahem, Menashe, Mendel, Mendes, Mepadova, Merdjan, Merendatcho, Meshulam, Meskina, Messeca, Messina, Meyerson, Miara, Miles, Miller, Minerbi, Minerbo, Miniuni, Mishael, Missisrano, Mistrial, Mitrani, Mizrahi, Mizrahi-Buiatchi, Mizrahi-Buiatcho, Mizrahi-Gordji, Mizrahi-Rebivo, Modai, Modiano, Mohlo, Molho, Molina, Monaje, Mondolfo, Mordehai, Mordo, Mordoh, Morguez, Moron, Moscona, Moshe, Mosseri, Motal, Motro, Munion, Mushel, Mussatche, Mussatche-Franco, Nadjari, Nadji, Nafussi, Nahamu, Nahbi, Nahman, Nahmias, Nahshon, Nahum, Namir, Naon, Nashahon, Nassi-Yakar, Natan, Natas, Navarro, Navarro-Pitchon, Negrin, Neter, Nevarro, Niego, Nigri, Ninio, Nissim, Nizama, Noah, Notrica, Orenfil, Ori, Ovadia, Oved, Padova, Palatche, Palermo, Palombo, Palti, Papo, Papushado, Pardo, Parnas, Pas, Pasharel, Pavon, Paz, Pelo, Penias, Penso, Perera, Perez, Perez-Badi, Perez-Badi, Pernidj, Pernidji, Perpegnan, Perpignal, Perpinial, Perpinian, Pessah, Pessoa, Petcho, Pilas, Pilo, Pilo-Aji, Pilos, Piperno, Pitchon, Pizante, Poiastro, Polaco, Poli, Policar, Politi, Politi-Argi, Ponpas, Pontremoli, Poyastro, Puentes, Raban, Rabi, Rahamim, Rahman, Ramas, Ramaz, Rebi, Refael, Reinal, Reiss, Renwil, Revah, Richer, Roditi, Rodric, Rodrig, Rodrigues, Rodring, Rofe, Romano, Romberg, Romero, Romi, Rosa, Rosales, Rosanes, Rosesfin, Rozio, Ruif, Russo, Saada, Saadi, Saadis, Saba, Saba, Sabal, Saban, Sabariego, Sadicaro, Sadis, Sadra, Sadras, Sadrina, Sadrinas, Saes, Sagues, Saidon, Salah, Salzir, Samanon, Sansolo, Saporta, Sarag, Saragossi, Saragosti, Sarda, Sarda, Sarfati, Sarfati-Tuvi, Sasporta, Sasson, Savariego, Saydon, Sazbon, Sedaca, Sedicaro, Segura, Segura [De], Selanikio, Semo, Seneor, Seninio, Senior, Sereno, Sereo, Serez, Sevi, Sevia, Shabetai, Shaki, Shalem, Shalish, Shalom, Shalom, Shalon, Shaltiel, Shami, Shaul, Shechem, Shehem, Shemaia, Shemaria, Shemaya, Shemtov, Shemuel, Sheneur, Sherez, Shikiar, Shikiartchi, Shikirtchioglu, Shimshon, Shinfield, Shipled, Shituvi, Shoel, Shonir, Shonshol, Shoshna, Shpierer, Shushan, Sid, Sidi, Sidicaro, Silvas, Simsolu, Sinai, Sinai-Eskenazi, Sinior, Sion, Solimani, Soncin, Soria, Soriano, Sorias, Spierer, Stires, Suhami, Sulam, Sulimani, Sultani, Suri, Surmani, Sussan, Sussi, Sustiel, Suzi, Taboh, Tacumi, Tacuni, Tadjer, Taitalak, Talvi, Tarabolos, Taragan, Taragano, Taranto, Tarica, Tarnera, Tazartes, Tchicurel, Tchigal, Tchiprut, Tchucrel, Tchucriel, Telias, Temimi, Teva, Tiano, Timkin, Toledano, Toledo, Torres, Tovi, Treves, Trevez, Triano, Turiel, Tuvi, Tuvi-Sarfat, Tuvi-Sarfati, Tzevi, Tzevia, Tzevi-Ashkenazi, Uberman, Ungar, Uriel, Usalvo, Uziel, Vaena, Valansi, Valensi, Vanstain, Varon, Veissid, Ventura, Verihori, Veycid, Vidas, Vinacor, Vital, Vurlas, Walman, Weiss, Wolfson, Yaacov, Yaavez, Yabetz, Yacoel, Yafe, Yafe-Eskenazi, Yahia, Yahini, Yahni, Yakar, Yatom, Yecutiel, Yehezkel, Yehuda, Yeini, Yerushalmi, Yeshurun, Yoel, Yohai, Yohanan, Yom, Yomtov, Yona, Yona-Eskenazi, Yossef, Zacuto, Zahar, Zaharof, Zaiefi, Zeevi, Zeharia, Zibil, Zisman.

The Family History Library has records of the Altindağ cemetery, 1934-1995.

Jewish Edirne

The city was historically also known as Adrianople. It suffered considerably during the various wars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and a fire in 1905. At the time of the fire, the Jewish population is reported to have been around 12,000 out of a total population of 80,000.

Some sources specifically on the Jews of Edirne include:

- In Search of a Jewish Community in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire: The Case of Edirne Jews (C. 1686- 1750) A Master’s Thesis by Gürer Karagedikli

- EDİRNE Its Jewish Community, and Alliance schools 1867-1937, by Erol Haker

Physical education at a Jewish school in Edirne, 1912

A view of Edirne showing Saraçlar Street, the Grand Bazaar, with the Jewish Quarter behind it.

Jewish Bursa

It is reported that a Turkish-language book, “Bursa Musevi Kaynakları (1839-1922)”, by Leyla Oral, is a collection of Jewish community records from the city of Bursa, including birth, marriage, and death records.

The Ets Ahayim Synagogue may pre-date the Ottoman conquest of Istanbul. By tradition, the Mayor Synagogue was established by Jews from Majorca. It is now used for events, and a section for washing the dead. The Gerush Synagogue, Altiparmak Caddesi No.20A, is in the old Jewish quarter. Reportedly it was built by Selim II for early refugees arriving from Spain. One source claims Jews mostly came from the Granada region.

The community’s cemetery is in the Kükürtlü neighborhood. It is believed to date back to the 16th century, and is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Turkey. The cemetery is still in use today, although many of the older graves have deteriorated over time. The cemetery contains several notable tombs, including those of Rabbi Moshe Ben Machir, who served as the chief rabbi of Bursa in the 17th century, and Rabbi Eliyahu Hazan, who was a prominent 19th-century scholar and community leader.

Interviews (in Turkish) with community members: 1 and 2.

Jewish Gallipoli

In Turkish, Gallipoli is Gelibolu. The city no longer has a Jewish community. Gallipoli Jews website is the best source of information. See also: https://kehilalinks.jewishgen.org/gallipoli/Gallipoli.htm

Gelibolu Yahudi Mezarlıgı by Fuat Durmuş is a 2020 Turkish-language book on Gallipoli’s Jewish cemetery. His master’s thesis was Osmanlı arşiv belgeleri ve arkeolojik kalıntılar ışığında Gelibolu Yahudi cemaati : yüksek lisans tezi

Ottoman Archives

Jonathan McCollum offers an introduction to Ottoman records for family history. The discussion of the archives starts at 9 minutes in.

See the takjensen channel on YouTube.

The Ottoman Archives are the great unknown of Sephardic genealogy. Below, largely using Google Translate, I have started the process of identifying what is where. I have contacts in Istanbul. If anyone wants to sponsor research, or is interested in using their own family history as a guinea pig, please let me know.

The guide to the Ottoman archives is #147, Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi Rehberi, İstanbul, 2017, 358 s. The Ottoman Archives’ database is at: http://www.devletarsivleri.gov.tr/

See “An Overview of the Ottoman Archival Documents and Chronicles” by Mehmet Mehdi Ilhan

Overview of Digital Sources For the study of the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Turkey by Nicole A.N.M. van Os

Guide on the General Directorate fo State Archives Ankara-2001

For general research in the Ottoman Archives, the principle resources are the Nüfus Defterleri (Population Books) and Tahrir Defterleri (Taxpayer Books).

Nüfus Defterleri (Population Books) were kept from 1831. Pre-1880 Population Books are kept in the Ottoman Archives. I am not sure if these earlier books included Jews, as the Jewish community kept their own records. The 19th Century Temettuât defterleridir (‘Profit’/’Income yielding asset’ books) are also in the Ottoman Archives. I am not sure what the Temettuât books contain. Population books from 1880 are in the Nüfus Genel Müdürlüğü Arşivi’ndedir (General Directorate of Population Archive). Also at the General Records are the ‘vukuat kayıtları’ which Google translates as ‘incident records’ and I am hoping mean vital records, as in Birth/Marriage/Death certificates. Provinces and districts also kept Population Books. In the later Ottoman period, censuses were conducted in various parts of the empire.

Tahrir Defterleri (Taxpayer Books). For the 15th to 17th Centuries, Tahrir books were kept by region. They record the men of the households, single men, widows, tax-exempt and elderly people who cannot pay taxes. Muslims and non-Muslims are recorded separately. Ethnicity has also been given in some regions. In Turkey, Taxpayer Books are in the Ottoman Archives in Istanbul and the Tapu-Kadastro Genel Müdürlüğü Arşivi (Archive of the General Directorate of Land Registry and Cadastre) in Ankara. However, family surnames are not recorded, just the father’s name.

Avarız defterlerinin (Avarız registers) contain tax records from the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Jews in the Ottoman Census

Below are partial results for Jews in the 1831 Ottoman Census. The results are mainly in the European part of the empire. A couple for Anatolia, but not Constantinople, Smyrna, Rhodes or several other major population centres. Nothing for Mesopotamia or the Middle East.

| Region | Jews |

| Rumeli Eyalet (Southern Balkans) | 9,955 |

| Selanik (Salonica) | 5,667 |

| Edirne (Andriople) | 1,541 |

| Manastir (Monastir / Bitola) | 1,163 |

| Republic of Bulgaria borders | 702 |

| Filibe (Plovdiv) | 344 |

| Siroz (Seres) | 248 |

| Silistre Eyalet (parts of modern Bulgaria and Romania) | 178 |

| Niğbolu Sancak (Nikopol) | 178 |

| Niš (Niš) | 178 |

| Köstendil (Kyustendil) | 145 |

| Pazarcik (Pazarcık) | 119 |

| Samokov (Samokov) | 94 |

| Çorlu (Çorlu) | 73 |

| Bergos | 51 |

| Total | 20,636 |

There was a census in Rumelia in 1844. A General Population Administration, attached to the Ministry of Interior was established in 1881/1882. The first modern census started in 1881/1882 and wasn’t completed until 1893. The population was counted by gender and ethno-religious groups, of which Jews were one. I believe the results were published in a volume entitled Devleti Aliye-i Osmaniye’nin 1313 Senesine Mahsus İstatistik-i Umumisi (The General Statistics of the State of the Ottoman Empire for the Year 1313).

A statistics authority, Istatistik-i Umumi Idaresi, was established in 1893. I have seen a claim that there was a census in 1899, but not seen any information about it. Maybe there was a local census somewhere.

A further census was undertaken in 1905-1906, in which an estimated 2-3 million people in Mesopotamia and the Middle East went uncounted. I suspect Jews were mainly in towns (perhaps excepting Kurdistan and the Caucasus) and were more likely to have been counted. The full results of the census were never published. Reportedly there were 253,435 – 256,003 Jews, comprising 1.24% – 1.23% of the population of the Ottoman Empire.

Some of the 1905 Census was destroyed in the Balkan Wars. There was an ‘oral census’, whatever that means, in the Republic of Turkey in 1925.

Ottoman Tax Registers (Tahrir Defterleri) by Metin M. CoÍgel

Ottoman-Dutch Economic Relations in the Early Modern Period 1571-1699, Mehmet Bulut lists sources he used.

I believe that court records (Şer’iyye Sicilleri) for some cities are in the National Library of Turkey (Millî Kütüphane) in Ankara. The researcher in Edirne lists the following as principle sources in the Ottoman Archives:

Kamil Kepeci Tasnifi

Maliyeden Müdevver Defterleri

Bab-ı Asafi Defterhane-i Amire Defterleri

Cevdet Tasnifi

Kamil Kepeci Tasnifi. Don’t know. Tasnifi may mean Classification.

Maliyeden Müdevver Defterleri. This is to do with finance.

Bab-ı Asafi Defterhane-i Amire Defterleri. I think this is the Office of the Grand Vizier, who would be sort of equivalent of a Prime Minister. The Bab-ı Asafi is the palace of the Grand Vizier. I think Amire is Imperial, so they may be synonyms, but not sure what this category includes. In modern Turkish, Defterleri means Notebooks, although the Defterdar had been the Grand Treasurer.

Cevdet Tasnifi. Hatt-ı hümayun (also called hatt-ı hümâyûn and hatt-ı şerîf) are documents from the Sultan’s personal office, often a response to correspondence or a petition. There were almost 100,000 of these. Historians have organised them into categories. One of these categories, Muallim Cevdet Tasnifi includes 216,572 documents in 34 volumes, organized by topics that include local governments, provincial administration, vakıf and internal security.

Family Search have a page on the Ottoman Empire Census.

Jewish Records in the Ottoman Archives

The Divan-ı Hümâyûn kept records of non-Muslim communities. Their Kilise Defterleri file may include records on the construction, repair and expansion of synagogues, schools, orphanages and cemeteries.

The Cizye Muhasebesi Kalemi was in charge of collecting the Jizya, a per capita tax levied on non-Muslim residents.

Emniyet-i Umumiye Müdüriyeti Yedinci Şube – the Seventh Branch of the Police Department – were concerned with Zionist activity in Ottoman Terra Santa.

Cadastal (Land Tax) Records. These are reportedly in the Cadastral Department Archives [Tapu ve Kadastro Umum Mudurlugu arsivi] in Ankara and Istanbul. Kadastro Genel Müdürlüğü Kuyûd-ı Kadime Arşivi’nde bulunan tahrir defterleri

Tapu Kadastro Genel Müdürlüğü Kuyûd-ı Kadime Arşivi’nde

The Young Turk Revolution was followed by the introduction of compulsory conscription, including for non-Muslims, in October 1909. This was greatly resented by Christian minorities, however my impression is that significant Jewish migration (at least to the UK) only happened in the 1920s followed the Greco-Turkish War, the devastation to the city of Izmir, and the establishment of the new Turkish Republic. Ataturk’s new republic abolished discrimination against religious minorities but required Turkish education, side-lining communal structures and organisations that had lasted centuries. Rather than being ‘Spanish Jews’, Sephardim were to be Turks who were Jewish.

Date converter for the Hijri calendar.

A series of videos on Turkish genealogical research.

Below is a presentation by the Ottoman Archives.

Archives of the different traditions of freemasonry is a possible source of information. A book on masonry in Turkey is LA FRANC-MAÇONNERIE D’OBÉDIENCE FRANÇAISE DANS L’EMPIRE OTTOMAN Ottomanisme, mouvements nationaux et “idées françaises” à l’âge de l’expansion coloniale de l’Europe by Paul Dumont.

I have seen this book advertised online, but it doesn’t look very useful: Search your Middle Eastern & European genealogy : in the former Ottoman Empire’s records and online by Anne Hart

Archives of the Ottoman Bank

Not reviewed these but may contain useful information. The Ottoman Bank Archives and Research Centre is part of SALT Research in Turkey. The London Metropolitan Archives have records from the London branch office. Very likely there are also records in Paris, and possibly some other European cities.

Reading the Ottoman-Turkish Language and Script

Obviously, a major challenge is the Ottoman-Turkish language, which was the language of the administration. I read that the best textbook for learning the language is The Routledge Introduction to Literary Ottoman by Korkut Buğday, but it is not cheap. I have also seen mention of Ottoman-Turkish Conversation-grammar: A Practical Method Of Learning The Ottoman-Turkish Language by H.V. Hagopian. A book published in 1884, and now freely available on Google, is A simplified grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish language by J.W. Redhouse. Redhouse also wrote a dictionary and lexicon, both free online.

There are now projects to make Ottoman archives more accessible. These include the Ottoman Text Recognition Network. I read that there are nineteen variants of Ottoman script, but Riqa (also Ruq’ah) appears to have been preferred for handwriting.

Below is a video presentation by Merve Tekgürler on applying Transkribus AI-driven text recognition software to Ottoman text.

I have read that there is a Turkish genealogical society called Türkiye Genealoji Araştırma ve Çalışma Grubu (Turkish Genealogy Research and Working Group) who have a publication called Soybilim Dergisi (Genealogy Magazine), but have found no information on them.

Ladino, Judeo-Spanish, Judezmo, Djudeoespanyol

This language of many names – an evolved form of medieval Spanish with inputs from other languages – was the vernacular of the Sephardic Jews of the Ottoman Empire, although in some places supplanted by French in the later period.

Sometimes Judeo-Spanish is mistakenly presented as being spoken by all Sephardim. Ladino was NOT the vernacular of the Western Sephardim who spoke Portuguese and Castilian Spanish or of the Megorashim of North Africa who spoke Haketia (sometimes confusingly also called Ladino), Arabic and French. There are other unrelated dialects called Ladino, including in Aragon and the southwest United States.

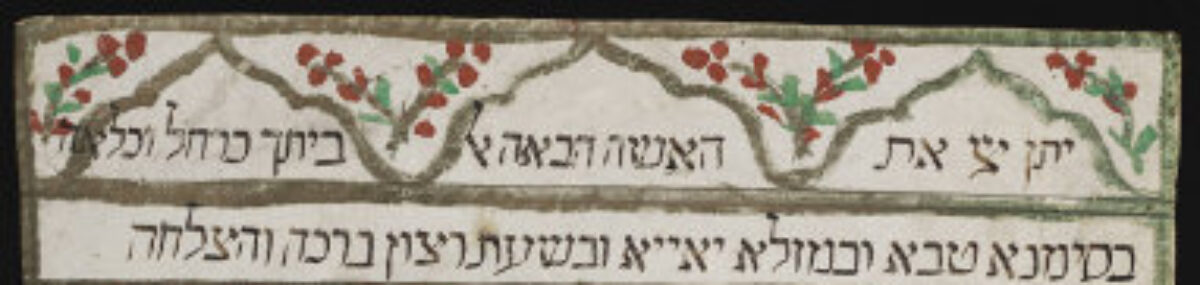

I am not sure how useful Judeo-Spanish is for general genealogy, but it is fascinating. Traditionally often printed in Rashi script and handwritten in Solitreo script, it is now often written in the Roman alphabet. Below is “Judeo-español” written in Solitreo and Rashi scripts.

Ladino suffered from the introduction of French as a language of Jewish education; migration to other countries; nationalisms in the countries of the former Ottoman Empire who required their own languages to be taught; and the Shoah.

Ladino is now an endangered language. The Stroum Center for Jewish Studies at the University of Washington is leading the effort to preserve Ladino. A Guide to Reading and Writing Judezmo by David Bunis can be downloaded. The soliteo.com website has resources on the language. Other Jewish communities in the Ottoman Empire spoke various dialects of Arabic, Greek, Kurdish, Aramaic and other languages.

If you have found this page on the Sephardic Jews of Turkey useful, please consider making a small donation to support this site and my work. Do you need a professional genealogist to work on your Sephardic genealogy? Click here.