Sephardic Jews of Aleppo

Aleppo had a mixed Jewish community including indigenous Mizrahi Jews, Eastern Sephardim, and ‘Francos’ (Western Sephardim). I have seen estimates that the community was 50-50 between these two communities, but not seen the evidence supporting the claim. I would guess that many or most of the Francos had connections to the Italian trading cities of Livorno and Venice, and with Marseilles and other West European trade interests.

Aleppo now has no Jews. Many synagogues were destroyed during the Bab al-Faraj project in 1995. These include the Beit Nas Synagogue, the Midrash Albumin Synagogue, and the Safra Synagogue. The Jews of Syria Facebook page lists synagogues in Aleppo.

Aleppo is an ancient city that stands on the old east-west Asian trade route, and was the last stop before Alexandretta (now Iskenderun in Turkey) and the Mediterranean. Aleppo is known as Haleb in Arabic, and Aleppan Jews are described as Halebi. Today Aleppo is part of Syria, but under the Ottoman Empire it was the capital of its own vilayet (province), which had equal status with the vilayet of Damascus.

Merchants from Aleppo settled in Western countries. In the UK, cloth merchants settled in Manchester. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 severely damaged the local economy by creating a faster and safer east-west trade route. Many Jews from Aleppo had already seen the writing the wall, or now left. Many settled in Egypt, where a thriving new Jewish community emerged. Others moved to Western countries. Some seem to have moved to Beirut. A significant, and somewhat isolationist, community was established in Brooklyn, New York.

After the Second World War, the ruptures caused by the collapse of the French Empire, Arab nationalism and the creation of the State of Israel resulted in the departure of remaining Jews. Much of the city of Aleppo was destroyed in the Syrian civil war that started in 2012. It was reported that the last Jewish family, the Halabi, left Aleppo to Israel in October 2015.

Sephardic Jewish Genealogy of Aleppo

Some Jewish records from Aleppo survive and have been transcribed by Sarina Roffe. These records can be found on the SephardicGen website, are being migrated to the JewishGen website. Places to look when researching family from Aleppo include:

Jewish Communal Records

- Aleppo Britot Milah (Circumcision) Database, 1868-1945

- Marriage Database from Aleppo, Syria

- Aleppo Jewish Surname Index compiled by Jacob Rosen-Koenigsbuch.

- Eulogies from Aleppo, Syria

- Tombstone Inscriptions of Aleppo Rabbis

- JewishGen has photos of 345 Aleppo Jewish gravestones.

- Family page of the Dayan family of Aleppo.

Other Records and Finding Aids

- The Cercle de Généalogie Juive in France is the centre of expertise on Syrian-Jewish genealogy.

- Syria Finding Aid of the AIU.

- Central Zionist Archives. This archive in Jerusalem, Israel has a significant collection of materials related to the Jewish community of Aleppo, including documents, photographs, and other materials. Their collections include the archives of the Jewish community of Aleppo from 1860 to 1959.

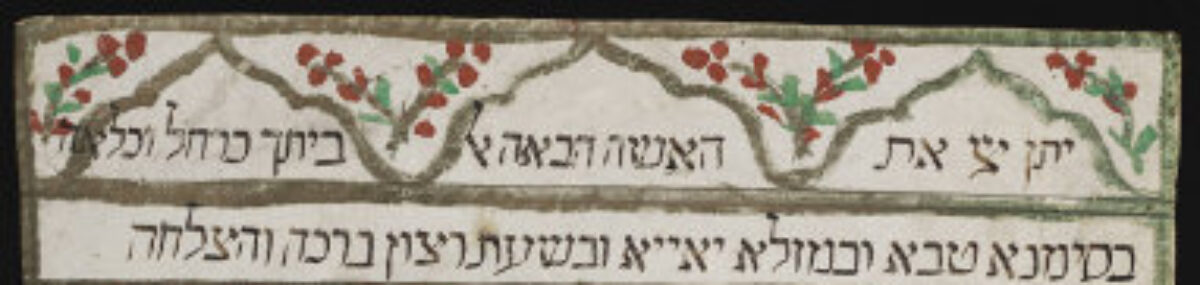

- National Library of Israel. This library in Jerusalem, Israel has a variety of materials related to the Jewish community of Aleppo, including manuscripts, books, and photographs. Their collection includes a significant number of manuscripts from the Aleppo Jewish community.

- Sephardic Heritage Museum, New York.

- Back to Aleppo. In 2023 the Israel Museum offered a virtual reality tour of Aleppo’s Great Synagogue.

- Sharia Court Records. I don’t know if the records of the Islamic courts of the city of Aleppo survived the Syrian civil war. Often non-Muslims appear in these records.

Foreign Consulates in Aleppo

In 1879, the following countries maintained consulates in Aleppo: Austria-Hungary, Belgium, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, The Netherlands, Persia, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Sweden & Norway, and the United States. Many Jews had citizenship of, or protection from, foreign countries. If you have a family memory of this, or your ancestors went to a specific country, or had an unexpected language from one of these countries, it is worth checking their consular archives. Sometimes these archives contain Birth, Marriage, Death records, and other documents related to their local communities.

Other useful records include those in the Ottoman Archives, French colonial records, the Alliance, memoirs, travel books, trade and journalistic reports and newspapers, Yad Vashem, and the archives of countries in which Halebi Jews later settled. For people of Western Sephardic (‘Franco‘) I draw special attention to the records of the early 18th Century Livorno company of Ergas and Silvera, studied by Francesca Trivellato in her book, The Familiarity of Strangers.

The Diarna website reports: “The Cemetery at Aleppo is located west of the city, in today’s Sulaymaniyya neighborhood. This communal cemetery supported the entire Jewish population until the Ottoman Empire released a decree in 1865 allowing Aleppo’s Jews to expand their community to match their growing population. At this time, the Jews added a cemetery for community leaders behind their synagogue. Today, both cemeteries have survived, and the Cemetery at Aleppo remains in the town’s Shaykh Maqṣūd district.” It is not known if the cemeteries have escaped damage in the Syrian civil war.

Civil Records for Aleppo

Ottoman Tax Registers (Tahrir Defterleri)

The Ottoman tax registers (tahrir defterleri) for Aleppo can be found in various archives and libraries, both in Turkey and internationally. Here are some possible places to look for these records:

The Ottoman Archives in Istanbul (Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivi): The Ottoman Archives in Istanbul have a vast collection of tax registers and other Ottoman administrative records. The registers for Aleppo may be found in the collection of Aleppo Province (Suriye Vilayeti) or in the collection of the Aleppo district (Aleppo Sancağı).

The British Library in London: The British Library holds a collection of Ottoman tax registers, including registers for Aleppo. These registers are part of the India Office Records and can be accessed through the British Library’s online catalog.

The Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris: The Bibliothèque nationale de France has a collection of Ottoman tax registers, including registers for Aleppo. These registers are part of the Département des Manuscrits collection and can be accessed through the library’s online catalog.

The Princeton University Library in New Jersey: The Princeton University Library holds a collection of Ottoman tax registers, including registers for Aleppo. These registers are part of the Garrett Collection and can be accessed through the library’s online catalog.

The Harvard University Library in Massachusetts: The Harvard University Library has a collection of Ottoman tax registers, including registers for Aleppo. These registers are part of the Islamic Heritage Project and can be accessed through the library’s online catalogue.

Civil Registration

Civil registration in Syria began during the Ottoman Empire in the mid-19th century, following the Tanzimat reforms of 1839. The Ottoman authorities established a centralized civil registration system in 1851, which required the registration of births, marriages, and deaths at the local level. The body in charge was the “Nufus ve Suret-i Defteri” (Population and Copying Register).

In 1920, the French established their own civil registration system, which was adopted by Syria after independence. It is believed that, under the French, civil registration records were kept by the local municipality or “mairie” with a copy submitted to central government in Damascus. So, it is possible that even if records have been destroyed in Aleppo, copies mark survive in Damascus.

The current Syrian civil registration law was enacted in 1957. The process is under the authority of the Ministry of Interior‘s Directorate of Civil Status and Passports.

Commercial Directories for Jewish Aleppo

Some commercial directories include:

- Almanach Commercial de Syrie et du Liban, published annually between 1912 and 1940.

- Annuaire du Commerce et de l’Industrie de Syrie, Liban et Haute-Mésopotamie, published between 1926 and 1946.

- Guide Industriel et Commercial de Syrie et du Liban

- Annuaire Oriental

- Guide SAM

Books on the Jews of Aleppo

“The Jews of Aleppo: Community, Culture, and Heritage” by Abraham Marcus and Joseph A. Levi: This book provides a comprehensive history of the Jewish community of Aleppo, from its origins to the present day. It covers topics such as religious practices, social organization, economic life, and cultural traditions.

“Aleppo Chronicles: The Story of the Unique Jewish Community of Aleppo” by Abraham Levy: This book is a personal account of the author’s experiences growing up in the Jewish community of Aleppo in the 20th century. It includes information on the community’s history, culture, and religious practices.

“Jewish Life in the Middle Ages” by Israel Abrahams: This book includes a chapter on the Jews of Aleppo during the medieval period, providing insights into their daily life, religious practices, and interactions with the wider community.

“The Sephardic Jews of Aleppo: Family, Community, and Nation” by Efraim Karsh: This book examines the social, cultural, and political history of the Jewish community of Aleppo, focusing on the period from the 16th to the 20th century.

“Les Juifs d’Alep” by Salomon M. Malka: This book provides a comprehensive history of the Jewish community of Aleppo, focusing on the period from the 16th to the 20th century. It covers topics such as religious practices, social organization, economic life, and cultural traditions.

ספר היהדות העלפית. “Sefer HaYahadut HaAleppit” (The Book of Aleppo Jewry) by Rabbi Shlomo Zalman Shragai: This is a comprehensive, multi-volume work that covers the history, customs, and traditions of the Jewish community of Aleppo from ancient times through the modern era.

היהודים בעלפו: תרבותם והנהגותם. “HaYehudim B’Aleppo: Tarbutam VeHanhagotam” (The Jews of Aleppo: Their Culture and Customs) by Rabbi David Yosef: This book provides a detailed examination of the religious practices, customs, and traditions of the Jewish community of Aleppo, with a focus on the period from the 16th to the 20th century.

Some old guidebooks to Aleppo, which hopefully report on Jewish Aleppo as it was include:

“Aleppo, Queen of the North” by Philip Khuri Hitti (English, 1944) – This guidebook provides a comprehensive overview of the history, culture, and attractions of Aleppo, including its architecture, markets, and religious sites.

“Le guide de voyage, Alep et ses environs” by Ernest Coindreau (French, 1924) – This guidebook includes detailed information on the sights and attractions of Aleppo and its surrounding areas, as well as practical advice for travelers.

“The Syrian Desert: Caravans, Travel and Exploration” by John Raphael Porter (English, 1911) – While not specifically a guidebook to Aleppo, this book provides a fascinating account of travel and exploration in the region, including descriptions of Aleppo and its people.

“A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine” by John Murray. Editions were published in 1858, 1868, 1875, 1884, and 1892. guidebook includes information on the major cities and sites of Syria, including Aleppo, as well as practical advice for travelers. Thomas Cook published “Cook’s Tourists’ Handbook for Palestine and Syria” in 1876. Baedeker published a competing guide, A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine, in 1894.

“Guide des étrangers dans la ville d’Alep” by Louis Vignes (French, 1845) – This early guidebook provides information on the history, architecture, and customs of Aleppo, as well as practical advice for foreign visitors.

Terms used in Ottoman Empire (in Arabic) by Dr. Mahmoud Amer, University of Damascus.

I am particularly interested in the Dweck / Dwek / Douek family of Aleppo. Various branches who do not know each other all claim Iberian origin, and cite a family tradition. I am looking for stronger evidence. If you can help, please send me an email.

Below is Sarina Roffe’s 2020 talk on the Jews of Aleppo, given to the Sephardic World group.

Travel Reportage on Aleppo

The Jewish population of the city was reported to comprise 1,500 to 2,000 families in 1860. Raphael de Picciotto was consul of Russia and Prussia and Elias Picciotto consul-general of Austria. The generosity of Salomon Lunjado [Lanyado] was commented upon. “The Jews dress here as they do in Palestine. They speak Arabic, but many of them also speak Hebrew with a so-called Portuguese accent, and likewise Italian with great fluency.”

The Church of England Magazine, page 366. VOL. XLVIII. January to June, 1860.

There are likely to be reports of the Jews of Aleppo in the Ottoman State Archives, consular reports of the European powers, reports of missionary and foreign Jewish organisations, and – once we get to the mid-19th Century – in trade directories, and records of foreign groups such as the freemasons.

If you have found this page useful, please consider making a small donation to support this site and my work. Do you need a professional genealogist to work on your Sephardic genealogy? Click here.